The Gherkin

A commentary by Nick Gent, a member of The Chelsea Society.

Eight members of the Society attended a walking tour arranged by the Society of some of the City of London’s prominent landmarks on Thursday 16th February 2017 at 11am. The meeting point was poignant, although apt in today’s uncertain times. We met at the Kindertransport memorial at Liverpool St. station. Just before the Second World War, ten thousand unaccompanied Jewish children were brought to Britain to escape persecution. These children arrived at Liverpool Street station, to be taken in by British families and foster homes. Only a few were reunited with their families after the war.

We were very fortunate to have as our guide, Raúl Curiel, retired director of the leading London architects, Aukett Swanke. He very kindly gave his time and expertise to afford us a fascinating insight into the planning and architectural aspects of some of the City’s iconic modern buildings and developments. Raúl was ideally placed to do so as his company has been actively involved with a number of the City’s high profile landmarks. For reasons of space, this note covers just some of the landmarks we saw on the walkabout but, hopefully, readers will have a flavour of what went on!

Group discussion in the Broadgate development

Raúl’s opening remarks were “the City is a machine for making money” and “must remain a money maker, given its pivotal role in the economy.” This point is, of course, true and it is in no small part due to the City’s powerful money-making abilities that we have such a fine array of architecture.

Starting in Liverpool Street station, Raúl emphasised the clever adaptation of the Victorian station to modern day use. He regards the station as a very good early example of the integration of new and old in London.

Already fired up with enthusiasm, we proceeded to the 1980s Broadgate office development, Phases 1 and 2, adjacent to the station. Visiting Phase I (Arup Associates, acting architects) comparisons were made between the different squares, which are at the heart of the development. Each one had a distinctive character. Raul impressed upon us the interplay between granite and sandstone and rectangles, circles and diagonal finishes and talked about “curtain walls” (non-load bearing walls) which afford more scope for aesthetic considerations in design. Despite the mixed styles, all the buildings seemed to fit together and complement each other well. Interestingly, Phase 2 (Skidmore, Owings and Merrill), which occurred seven years after Phase 1, coincided with the advent of money from the United States. This heralded a change in style, characterised by bigger buildings and some pastiche.

In marked contrast to our experience in Broadgate, where building height is restricted to around ten storeys, Raúl introduced us to the Heron Tower (Kohn Pedersen Fox). This building is in what is known as the “tower district”, located in Bishopsgate, one of the tallest buildings in the City, 47 storeys, rising to a height of over 200 metres. Of particular interest, the building is divided into ten three-storey “vertical villages”, each with accommodation arranged around a central atrium and facilitating distinctive cultures.

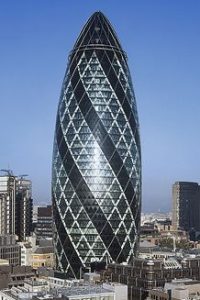

Still in the tower district, we visited The Gherkin, in St Mary Axe (Foster and Partners), not quite as tall as Heron Tower, 41 storeys and 180 metres high. This is a beautiful landmark, whether seen from afar or at close quarters. Still in the same area, we saw the Cheese Grater, 48 storeys and 225 metres high, and the Lloyd’s of London building, just 14 storeys and 88 metres high. The architects to both these buildings are Richard Rogers and Partners, a singular achievement as the buildings are not only adjacent to each other but built in different eras, the former in 2013 and the latter in 1986. The Cheese Grater is in the form of a wedge shape to respect the “strategic sightlines” of St Paul’s (from Richmond and Parliament Hill). The Lloyd’s of London building was regarded as the first modern building in the City, indeed, I recall it attracting a lot of column inches, all those years ago!

Across from The Gherkin, we passed by one of Raúl’s firm’s own buildings, Exchequer Court at St Mary Axe; he described it as an example of the transitional design prevalent in the City in the 1990’s.

After repairing to the Royal Exchange (redeveloped and extended by Raúl’s practice), in Bank, for a well-deserved lunch, we headed for our last destination, Paternoster Square, by St Paul’s Cathedral. This took shape in the 1990s and has had somewhat mixed reviews. Amongst our group, it was thought that the square was a bit “soulless” and that we were not drawn into the square in the same way as we were with Broadgate, in the morning. After a good lunch and a day of tutelage from Raúl, I think it is fair to say that we felt we were better qualified to make such a value judgement than at the start of the day!

To finish, and to make a personal point, it is wonderful that the Chelsea Society organises tours such as this one as it makes one more appreciative of, and enjoy more, what surrounds us. Such events complement admirably the conservation role of the Society.