Summer 1940 – June Spencer, a debutante and dress designer, volunteers as a driver for the London Auxiliary Ambulance Service in Chelsea. It’s gruesome dangerous and frightening work, but off duty she appears to rise above it. “My life off-duty was like another world. I’d be shopping in the West End, dining at the Ritz, wearing smart dresses, going to balls, generally enjoying the social scene that I had just been introduced to when I was presented to the King.”

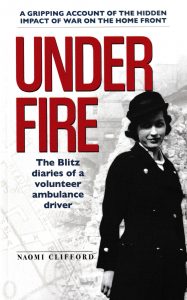

A book about her experiences, written by Naomi Clifford and based on June’s diaries, will be published by Caret Press on 7th September.

June’s experiences are remarkably similar to those of Marie Vassilchikov, and recalled in her “Berlin Diaries.” Instead of relaxing away from the war at country estates these two young women preferred to be in the middle of the appalling tragedy and devastation of London and Berlin.

In Chelsea “The dark and now alien landscape of broken bricks and masonry, open stairs and gaps, falling beams and escaping gas was a minefield of hazards. The surrounding cacophony was impossible to ignore – bombers droning above, AA guns firing, high explosive bombs shrieking while walls fell, rescue workers sawed and drilled and shouted instructions to each other, and the trapped and wounded coughed up the dust in their lungs and cried for help.”

A shelter received a direct hit in Beaufort St. A dead baby had been found but there was no way to identify the mother so the rescue workers placed the little body in the arms of a dead woman they had found. A high explosive bomb fell through the roof into the crypt of the Catholic Church of the most Holy Redeemer in Upper Cheyne Row, killing 19 people sheltering there – mostly women and children.

June never described in detail her feelings on seeing dead bodies or parts of them but she told her family of returning to her lodgings in Lindsey House on Cheyne Walk, owned at that time by the enigmatic antiquarian and seafarer, Richard Stewart-Jones. “Did you have a nice day they would ask” all you could say was “yes thank you” because ambulance workers were under strict instructions not to give away information.

Above Chelsea was the sound of enemy planes in a sky criss-crossed with tracer bullets. In front of the ambulance the hazards of the blackout. While starlight or moonlight might help a bit, the darkness was intense – illuminated if the driver was lucky by the flash of gunfire or the phosphorescent glow of incendiary bombs. In Bramerton St. the casualties included the family of Dr. Richard Castillo a local GP. Four days after the bomb fell 12-year-old Mildred Castillo was found alive and conscious but pinned by the neck, arms and legs, by timbers which were supporting tonnes of debris.

“Tuesday 17th September terrific gun barrage. A spy had been shot for signalling from the top of the Lots Road power station.” That nervy edge – twitchiness about who was letting the side down or was not entirely loyal affected everyone, even at the ambulance station.

“On the embankment just under Thomas Carlyle’s statue Royal Engineers were working on an unexploded bomb. They pulled me over the fence to look at it. It was 20 feet down – a soldier was sitting on it and another was swinging over the hole on a rope.”

12th November 1940 “a bomb fell on the rear carriage of a train as it was leaving Sloane Square tube station, and the blast went along the tunnel, propelling the rest of the train almost to the next station. Sloane Square was strewn with glass, flaming jets from a gas main, and the ultramodern newly-designed Peter Jones building standing proudly without a pane of its acres of glass broken.” The editors of the John Lewis magazine said “we shall defend our partnership with the utmost energy. What matter if we are bombed out of John Lewis – we shall fight on at Peter Jones.”

“This is certainly hell and no mistake – hardly a minute’s pause between each load of bombs and each one sounding as if it’s going to hit our house. Gosh it’s awful – this is the heaviest bombing we’ve had since the war began – the absolute poetry of destruction.” The trees across the water in Battersea Park were ablaze and the sky glowed red with shooting flames. The river looked as if it were on fire.

One of June’s close friends was A.P. Herbert, who kept a boat called “Water Gypsy” at Cadogan Pier, and like many wartime friendships it was fuelled by circumstances of time and place. Herbert was kind clever and funny and a misfit. Perhaps June found contradictory elements of safety and illicitness in their friendship – sparks missing from the other more conventional men who had so far courted her. Another friend was James Lees-Milne.

While June was in the ballroom of Grosvenor House, a mile away near Leicester Square a bomb fell through the Rialto cinema, down a ventilation shaft and into the Café de Paris where it exploded. At least 34 people were killed, some literally blasted to pieces, others unmarked – the air sucked out of their lungs. The couples lying on the dance-floor looked like beautiful dolls that had been broken and the sawdust had come out.

16th April 1941 an aerial mine hit the Royal Hospital Infirmary destroying the east wing. 40 people were trapped and the rest of the building was so badly damaged that it was later demolished. 4 nurses the Wardmaster and 8 Chelsea Pensioners died and 37 others were injured. There were scores more people trapped in nearby buildings in Tite Street and Cheyne Place

At 1:20 AM two huge explosions were heard close together. The wardens went out to investigate and saw in the moonlight that the Old Church, the heart of Chelsea village, was gone. The parachute mine had destroyed the massive tower leaving a jagged stump of brickwork and timbers. While the smell of bonfires and cordite hung in the air emergency workers downed whiskies in the Cross Keys pub – then missing a wall.

June showed an astonishing cool-headedness when she drove through London under a shower of bombs. She could have been killed at any time yet she continued to report for duty as required – ready to do it all over again.