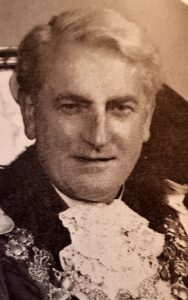

Basil Futvoye Marsden-Smedley (1901 – September 1964) was a barrister and local politician active in Chelsea.

The younger son of John Marsden-Smedley of Derbyshire, Basil was born and lived his entire adult life in Chelsea.

He was educated at Harrow School and the University of Cambridge and was called to the bar at the Inner Temple. At the age of 16 he lost the use of his right arm.

In 1927 he married Hester Harriet, eldest daughter of Major-General Sir Reginald Pinney.

From 1928 until his death he was a Municipal Reform Party (later Conservative Party) member of Chelsea Borough Council, and served as Mayor of Chelsea for two consecutive terms in 1957-59.

He was also a long-term member of the London County Council, elected unopposed to fill a casual vacancy in the representation of Chelsea on 23 February 1933. He was re-elected twice, retiring from the County Council at the 1946 elections.

He was awarded the OBE in the 1944 Birthday Honours for his work as “Adviser to Postal and Telegraph Censorship, Ministry of Economic Warfare”.

When the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea was formed as a shadow authority to replace the Borough of Chelsea from 1 April 1965, Marsden-Smedley was chosen as an Alderman.

The following tributes were paid to Basil Marsden-Smedley at the Society’s 1964 Annual General Meeting

Lord Normanbrook said:–

“We in the Chelsea Society had suffered a grievous loss by the death of our late Chairman, Basil Marsden-Smedley. In his wide circle of his friends, and indeed in Chelsea as whole, it left a gap hard to fill.

The social life of this country had been based for many generations on the principle of voluntary public service, and Basil was a shining example of the application of this principle.

The greater part of his adult life was devoted to the service of the community in which he lived. He loved Chelsea but he was not content to live in it and enjoy it. He worked actively and ceaselessly to keep it as a place in which we could all be proud and happy to live. This was an absorbing interest in his life and he pursued it with selfless devotion.

To further the interests of Chelsea and to preserve its amenities, he was always ready to undertake any duty however laborious, any task however tedious, any research however meticulous and detailed, any negotiation however difficult or delicate. No time was too long for him to spend, no trouble too great for him to take so long as he was working for the good of Chelsea as he saw it.

As members of the Society, we owed him a great debt. He was tireless in his work for it. Indeed it was not too much to say that he became in himself a personification of the Society. He will long be remembered in Chelsea, not only for his record of public service to the community, but also as a well-loved and loyal friend. A gentle and kindly man, unmoved by personal ambition or private interest, he was always ready to help others, and to give his advice or assistance in the furtherance of a good cause.

Lord Conesford said:

The Chelsea Society is 37 years old. I do not know any Civic or Amenity Society which has had a more precious place to serve or protect, or which has fought harder to serve and protect it. Sometimes it has succeeded and sometimes it has failed. Whatever follies the vandals have committed, this, I think, is certain: but for the work of the Chelsea Society, one of the most beautiful and far-famed parts of our capital would today be incomparably poorer. Such success as we have had we owe to a few devoted and remarkable men, Reginald Blunt, our founder, St. John Hornby, our Chairman for 16 years, Richard Stewart Jones and Basil Marsden Smedley.

Of all these great servants of the Society, Basil served it longest. He was a member of the Council for 30 years and its Chairman for the last 19, with the exception of the two years when he was Mayor of Chelsea, during which l served as Chairman. I served on the Council from 1946 to 1962, with the exception of the years when I was a Minister, and I thus had the experience of working with him for twelve years.

What were his qualities, as I see them? First, an immense love of Chelsea and the most intimate knowledge of it. He knew its architecture, its trees, its squares and terraces, its history, its industries, past and present, and its arts. Secondly, he was vigilant, well informed and immensely hard-working. Aided by a large number of friends in all sections of Chelsea society, he frequently had the earliest intimation of possible threats to the things he loved and took timely and appropriate action. Let me quote, and apply to Basil, a few sentences from St. John Hornby’s beautiful tribute to Reginald Blunt.

“As the years went by he could not help looking with a sad eye on the passing away of many an ancient land-mark and cherished building. For to him Chelsea was something almost sacred, and though he realised that changes must come and that some destruction of what was old was inevitable for he was in no sense narrow-minded -he was, so far as Chelsea was concerned, like a jealous lover with his mistress, and could not bear to see wanton hands laid upon her. Like a knight of old he sprang at once to arms when she was threatened and waged a doughty fight for her deliverance.”

Thirdly. Basil was indefatigable in attending public Inquries and the like and representing our views.

Fourthly, he was very good at writing a timely letter to the Press, where needed, and in giving information to friends of Chelsea in Parliament, when it seemed that a Parliamentary Question or Parliamentary action might help.

Lastly, he produced a series of admirable and attractive Annual Reports, which I believe members greatly value, and which are among the rewards of membership .

None of these things, I know, can convey the man we knew. Many of his qualities would be rare in themselves; they are rarer still in such happy combination.

The other day I was reading Thucydides and came to a passage which I had almost forgotten. Early in the Funeral Oration Pericles said “It is difficult to say neither too little nor too much; and even moderation is apt not to give the impression of truthfulness. The friend of the dead who knows the facts is likely to think the words of the speaker fall short of his knowledge and of his wishes; another who is not so well informed, when he hears of anything which surpasses his own powers, will be envious and will suspect exaggeration.”

Today, in describing Basil’s work, I have not exaggerated. I would say this in conclusion. If a man can be as widely known as Basil was in an area us small as Chelsea, where he has long lived and worked, and if he can there command such general respect and affection, he has achieved one of the rarest of honours that our present civilisation can bestow.